Constraints Tutorial

KEYWORDS: DESIGN GENERAL

Tutorial by Frank David Teets (frankdt@email.unc.edu). Edited by Sebastian Rämisch (raemisch@scripps.edu) and Kristin Blacklock (kristin.blacklock@rutgers.edu). File created 21 June 2016 as part of the 2016 Documentation eXtreme Rosetta Workshop (XRW).

Many of the biological problems users wish to solve with Rosetta involve some biological or functional considerations that may not be reflected within a PDB file or evaluated by normal score functions. Constraints are a general way of scoring how well a structure adheres to these additional considerations; for example, one might wish to relax a structure with constraints in place to ensure that suspected disulfides are maintained.

Constraints work in the following way:

- Some measure is calculated in a given conformation (e.g. 3.2 A)

- There is a suitable function that describes which values are good and which ones are bad, e.g. the ideal bond length could be the minimum of a parabolic function (harmonic potential). By evaluating the function for the measured value, a penalty is calculated. For the harmonic potential, the penalty increases the further away the measured bond length is from the ideal length.

- This penalty is multiplied by a weighting factor and added to the energy.

For example, a simple constraint might be set up to measure the distance between two atoms, subtract the ideal distance, and subtract the difference from the score. That constraint would look like this:

AtomPair CA 20 CA 6 LINEAR_PENALTY 9.0 0 0 1.0

This constraint definition is composed of two parts. AtomPair CA 20 CA 6 indicates what is to be measured, whereas LINEAR_PENALTY 9.0 0 0 1.0 1.0 defines how to turn that measurement into an energetic penalty.

The constraint begins with the definition of the geometrical property to measure. In this case, since we want to constrain two atoms to be a specific distance away from each other, we want an AtomPair constraint. The next four fields are parameter to the AtomPair constraint. Specifically, we define the two atoms that are to be constrained as the alpha-carbons of residues 20 and 6 (in Rosetta numbering).

After the parameters for the constraint comes the definition of the function which transforms the measurement into an energetic penalty. Here we're using the LINEAR_PENALTY function. The parameters which come after the function selection provide details on the functional form. The first parameter to LINEAR_PENALTY indicates that the lowest energy is when the atoms are 9.0 Angstroms apart. If this structure were "perfect" according to the constraints, the alpha-carbons of residues 6 and 20 would be 9A apart. The remaining field define how the score changes as we vary from the 9.0 Angstrom ideal. For LINEAR_PENALTY, that score increases linearly with the (absolute) difference from the ideal value. The slope can be controlled by the fouth parameter to LINEAR_PENALTY (here 1.0). LINEAR_PENALTY also includes the ability to add a flat zone in which the function returns a constant value. Here, that value is 0, and the width of the flat zone is also 0.

To demonstrate this, begin by relaxing ubiquitin via the following command:

$> $ROSETTA3/bin/relax.default.linuxclangrelease -s 1ubq.pdb -out:suffix _unconstrained @general_relax_flags

as in the relax tutorial and compare the output to that of

$> $ROSETTA3/bin/relax.default.linuxclangrelease -s 1ubq.pdb @general_relax_flags -out:suffix _unreasonably_constrained @unreasonable_constraint_flags

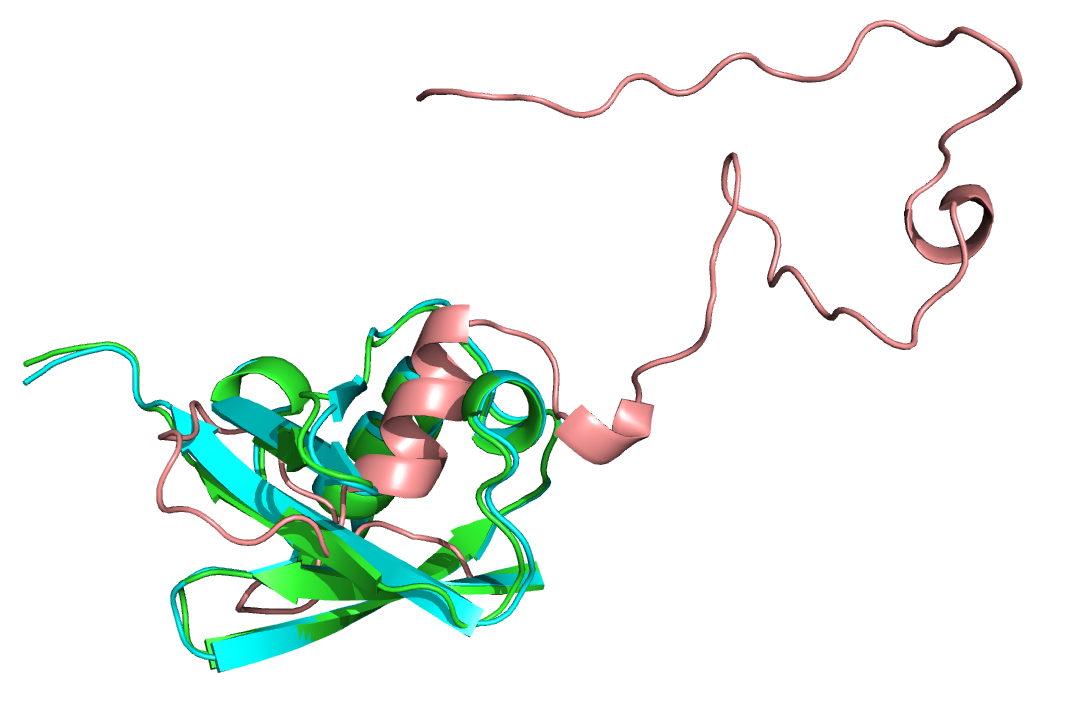

The native PDB 1UBQ (cyan), unconstrained refined version (green) and unreasonably constrained refined version (salmon).

In the unreasonable_constraint_flags file, try changing the weight of the constraint using the -constraint:cst_fa_weight flag and analyzing how this changes the final structure. High (>1000) weights should produce demonstrably aphysical structures, unless you set the constraint ideal to something close to its native value. It is important to select a weight in proportion to the expected score value and how much you want your results to fit the constraint; a preparatory Relax run should give you an idea of the expected score range. It is also important that the constraint function chosen reflect any uncertainty about the biological system, for which reason there exist "flat" versions of several constraint functions (LINEAR_PENALTY and HARMONIC among them) which allow for any value within a range to count equivalently.

Commonly Used Constraints

AtomPair and AtomAngle constraints are parameterized as described above, although AtomAngle constraints require three atoms (with the vertex atom listed second.) AtomPair and AtomAngle constraints to sidechain atoms are not robust to residue identity changes. The constraints are set up based on the atom identities in the starting structure. When the residue changes, this correspondence may become inaccurate. NamedAtomPair and NamedAtomAngle constraints exist which will always constrain the named atoms, even when the residue identity changes. AtomPair/NamedAtomPair values are returned in Angstroms, while AtomAngle/NamedAtomAngle results are returned in radians.

CoordinateConstraints work like AtomPair constraints, except the second "atom" is a point in 3D space rather than an actual atom. Since Rosetta uses relative coordinates, CoordinateConstraints require a second atom to define the coordinate frame; this second atom should not be one expected to move in concert with the first, but need not be any particular distance away from it. The related LocalCoordinateConstraint uses three more atoms to define the coordinate frame. These may be used straightforwardly in Relax runs via constrain_to_native_coords.

Commonly Used Constraint Functions

HARMONIC constraints square the distance between the ideal and actual value, and are commonly used for various types of distance constraints. CIRCULARHARMONIC is the angular equivalent.

Other constraints that Rosetta can handle:

- Distance constraints

- Torsional constraints

- Other angle constraints

- Ambiguous constraints

- Density constraints

To learn more about the other constraint types and function types that Rosetta can impose, see the constraint file documentation.

How to Use Constraints

As mentioned above, constraints are a way to make Rosetta's scores reflect some experimental data about the system being scored (or designed) and disfavor structures that would conflict with that data. As an example, suppose we wish to relax one half of a protein-protein interaction, but we know, perhaps from mutational studies, that certain residues on each subunit interact. It may make sense to include that information via constraints, which might look like this:

AtomPair CA 356A CA 423B HARMONIC 4.3 0.25 1

AtomPair CA 432A CA 356B HARMONIC 4.3 0.25 1

To demonstrate this, run

$> $ROSETTA3/bin/relax.default.linuxclangrelease -s 4eq1.pdb -out:suffix _unconstrained -ignore_unrecognized_res @general_relax_flags

and

$> $ROSETTA3/bin/relax.default.linuxclangrelease -s 4eq1.pdb -out:suffix _constrained -ignore_unrecognized_res @general_relax_flags @constraint_flags

You should see that, while the rest of each subunit moves, the N-terminus of each subunit moves very little relative to residue 423, as per the constraints we entered. (You may verify this more rigorously by measuring the distance from residue 356 to residue 423 on the other subunit.) As mentioned previously in the relax tutorial, if we wished to prevent any of the amino acids from moving particularly far from their starting position, we could use the option

-relax:constrain_to_starting_coords